A Backwards Journey to Becoming a Ninja – Antony Cummins

I started at the end. I was going to be a ninja. Standing in the doorway of an ancient master’s dojo in Japan, dreams stood

They assail us from news headlines announcing their crimes, big and small. In Hollywood’s sepia-toned renderings of said crimes, they prance about in khaki or olive-green uniforms, chests weighted down with medals, eyes keen on treachery and murder. On social media, they fill our ears and eyes with vacuous promises while their children jet across the world, partying with the rich and famous, slapping us in the face with the spoils of their parent’s corruption. In the streets of the continent’s cities, towns and villages, their faces adorn ankara-print cloth, splayed across busts and bottoms to commemorate national and personal events. In the homes, schools, hospitals and offices of the same cities, towns and villages, their policies (or lack thereof) create mind-boggling amounts of suffering. These days, one can hardly escape the vagaries African political figures. In the last three quarters of a century since African peoples began to declare independence from European colonial control, African political leaders have transformed from dignified figures of African emancipation to the sometimes unwitting, but often all too willing orchestrators of the continent’s ruin. The idea of a living politician from the continent writing a book of folklore espousing traditional values today and being taken seriously is about as credible as the idea of flying pigs. This is why I find the many case of the African Statesman-as-Folklorist particularly interesting.

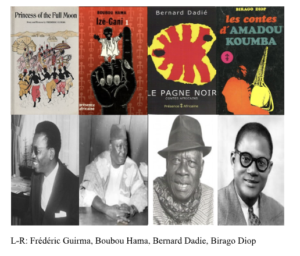

I first came across this phenomenon while curating Mythological Africans (or MA), an online platform where I explore mythology, folklore, spirituality, and culture from the African continent. One of MA’s most exciting projects was Anansi Book Club, an African folklore reading club which I co-ran from 2022 and 2023 with my friend, educator and mythologist, Laura Gibbs. In July 2022, we read “Princess of the Full Moon” a beautifully illustrated folktale by Burkinabé author Frédéric Guirma. Imagine my surprise when I found out that in addition to writing and illustrating books of folklore, Frédéric Guirma (who passed away in January 2024), also had quite the illustrious career as a politician and a diplomat. He served as the President of his country’s National Trade Union, and as their first Ambassador to the United States and Representative to the United Nations. He also headed the conservative political party and contested in the country’s 1998 presidential elections.

Frédéric Guirma is in good company. As independence movements swept across the continent, the architects of these movements paid close attention to crafting cultural narratives which highlighted the best of their traditional cultures. This approach epitomized the Négritude movement which emerged from former French colonies, perhaps as a deliberate pushback against the devastating French colonial policy of assimilation. Some of the next couple of names I mention will certainly sound like a roll call for the Négritude movement!

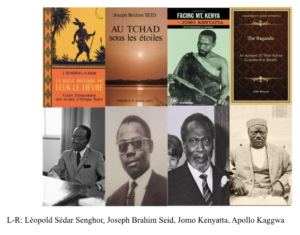

From Niger, which borders Burkina Faso to the east, Boubou Hama who served as the President of the National Assembly of Niger from 1958 to 1974, was also a prolific and award-winning author. He wrote over 40 books, one of which is Izé-Gani, the story of a little boy (no bigger than his mother’s forefinger!) who, nonetheless, looms large in the folkloric account which draws from Boubou Hama’s Songhay and other West African origins. Izé-Gani is an “Enfant Terrible.” These quintessentially African folkloric figures combine the characteristics of a trickster/hero/anti-hero into unforgettable characters through which traditional norms are interrogated and when necessary, changed or even discarded. From Côte d’Ivoire in the southwest, Bernard Binlin Dadié who served Ivorian Minister of Culture from 1977 to 1986, wrote “Le Pagne Noir: Contes Africains” (The Black Cloth: African Folktales). This is a collection of known and original stories inspired by the folk narratives of Anyin and Nzema speaking people in Côte d’Ivoire. To Burkina Faso’s north, Birago Diop and Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal are some of the African continent’s most recognizable scholars and authors. Birago Diop published five folktale collections including “Les Contes d’Amadou Koumba” (Tales of Amadou Koumba) which he transcribed from the accounts provided by his family’s griot, Amadou Koumba. His other collections also include stories he heard and committed to memory while working in the field as a government agricultural inspector. Birago Diop also published poems, dramas and commentaries which drew inspiration from the mythology and folklore of his native Wolof and other West African peoples. Léopold Sédar Senghor’s “La Belle Histoire de Leuk-le-Lièvre” (The Beautiful Story of Leuk-le-Lièvre) was coauthored with Abdoulaye Sadji, another distinguished Senegalese author of that era. “The Beautiful Story of Leuk-le-Lièvre” is possibly the most widely adapted work of folklore from the continent. This rollicking account of the adventures of Leuk the Hare has an audio-disc complete with musical accompaniment, an illustrated 48-page booklet, and a guide for teachers. It also inspired the French-Canadian animated series Samba and Leuk the Hare which, as it turns out, was a childhood favorite of mine! Both Birago Diop and Léopold Sédar Senghor also held public office. Birago Diop served as his country’s first ambassador to Tunisia from 1960 to 1965. Léopold Sédar Senghor rose in the post-colonial Senegalese political ranks to eventually become the first ever president of the country. He held the position for two decades.

The Statesman-as-Folklorist phenomenon was not limited to West Africa. In Central Africa, Joseph Brahim Seid from Chad authored “Au Tchad Sous les Étoiles” (Told by Starlight in Chad), a collection of likely romanticized but still quite enjoyable folktales he heard told as a child. He also served as the Minister of Justice from 1966 to 1975. In Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta who served as his country’s Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and then as its first President from 1964 to 1978, also authored “Facing Mt. Kenya” a detailed anthropological study of his native Gĩkũyũ people. The book is threaded with folkloric accounts including the Gĩkũyũ creation myth. From nearby Uganda, Apollo Kaggwa who, in the late 1800s and early 1900s served as Katikkiro (Prime Minister) of the Kingdom of Buganda under King Mwanga II, is also the best known ethnographer from the country. He wrote five books on these topics including Engero z’Abaganda, a book of Baganda folklore. He is widely credited as the source of most of the available documented history, legend and folklore of the Baganda. British missionary and anthropologist John Roscoe, who also wrote extensively about the Baganda, references Apollo Kaggwa as the source of much of his accounts. In his 1911 book “The Baganda: An Account of their Native Customs and Beliefs”, Roscoe explains that since war and famine had killed most of the old men who knew the most about the former religious customs, Apollo Kaggwa had old people brought from as far away as sixty and sometimes a hundred miles, and entertained them for several weeks at a time so he could talk with them and record their accounts. Finally, from South Africa, there is Nelson Mandela, whose passionate and principled fight against his country’s racist apartheid regime led to his imprisonment and eventual ascendance to presidency. He wrote “Nelson Mandela’s Favorite African Folktales,” a vividly illustrated and family-friendly collection of some of the best known and most beloved stories from the continent.

If there are no women on this list, it is simply because the African political arena was and is still largely a male dominated field. However, credit is likely owed to the mothers, grandmothers, aunties, sisters and other female relatives under whose care and from whose lips these men almost certainly heard most of the stories they include in their accounts.

I doubt any of the individuals included in this discussion were perfect politicians (if such a thing even exists). Matter of fact, in 1962, a mere two years into his presidency, the Senegalese High Court sentenced Léopold Senghor’s main political rival Mamadou Dia to prison for 20 years, in what was decried as a mistrial of justice. Also, by some accounts, Apollo Kaggwa betrayed his regent, King Mwanga II and leaves behind a complicated legacy. Nonetheless, together, these works offer a hope-filled glimpse into what some of the then architects of post-colonial African societies hoped would fuel the dreams of subsequent generations. Perhaps, their successors should take note.

This blog was written by Helen Nde, author of The Watkins Book of African Folklore which is publishing 11th March 2025 and is available to preorder now.

I started at the end. I was going to be a ninja. Standing in the doorway of an ancient master’s dojo in Japan, dreams stood

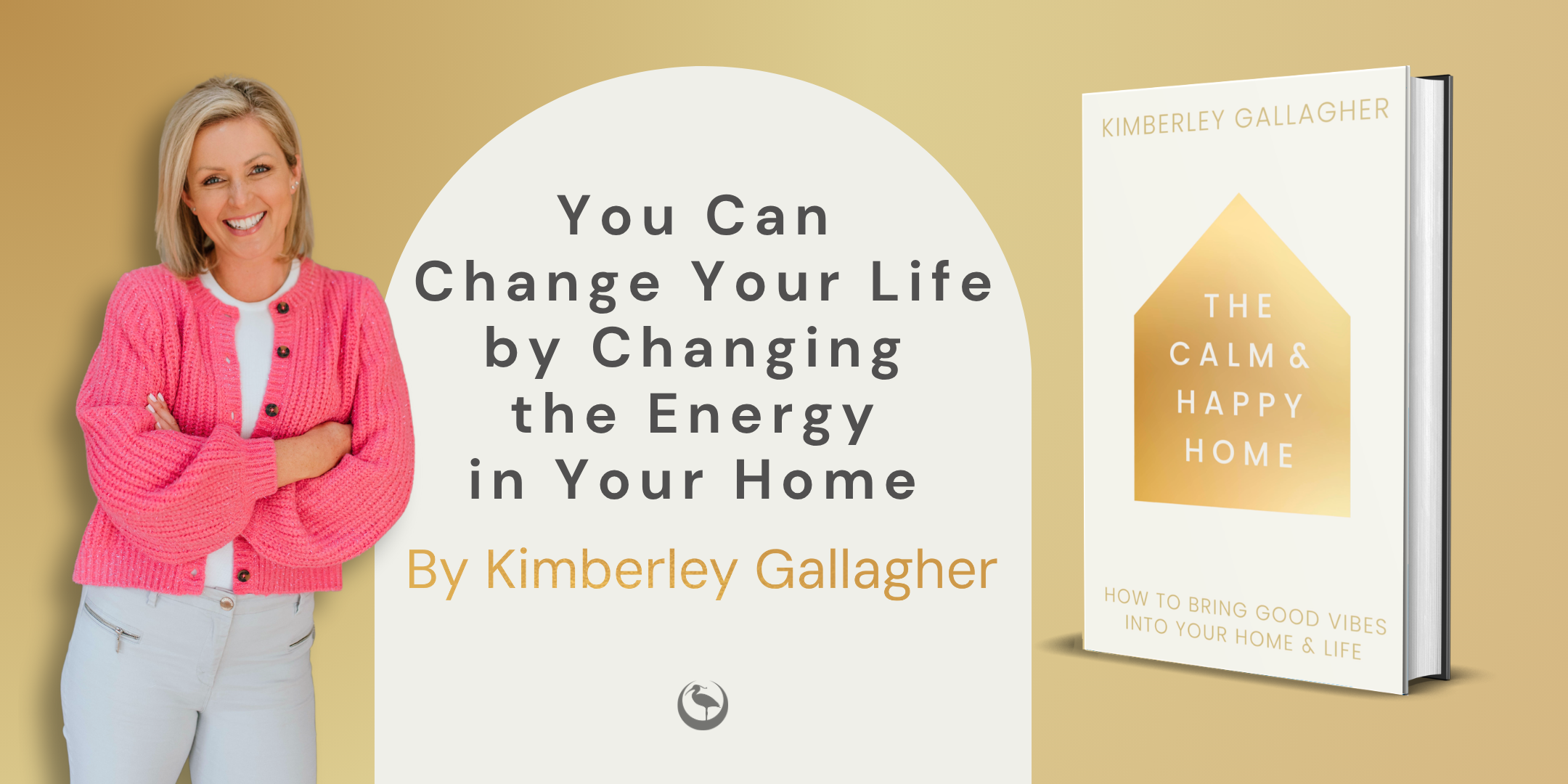

If I asked you to describe your home, what words would you use? You might tell say it’s an apartment, a cottage, or a townhouse.

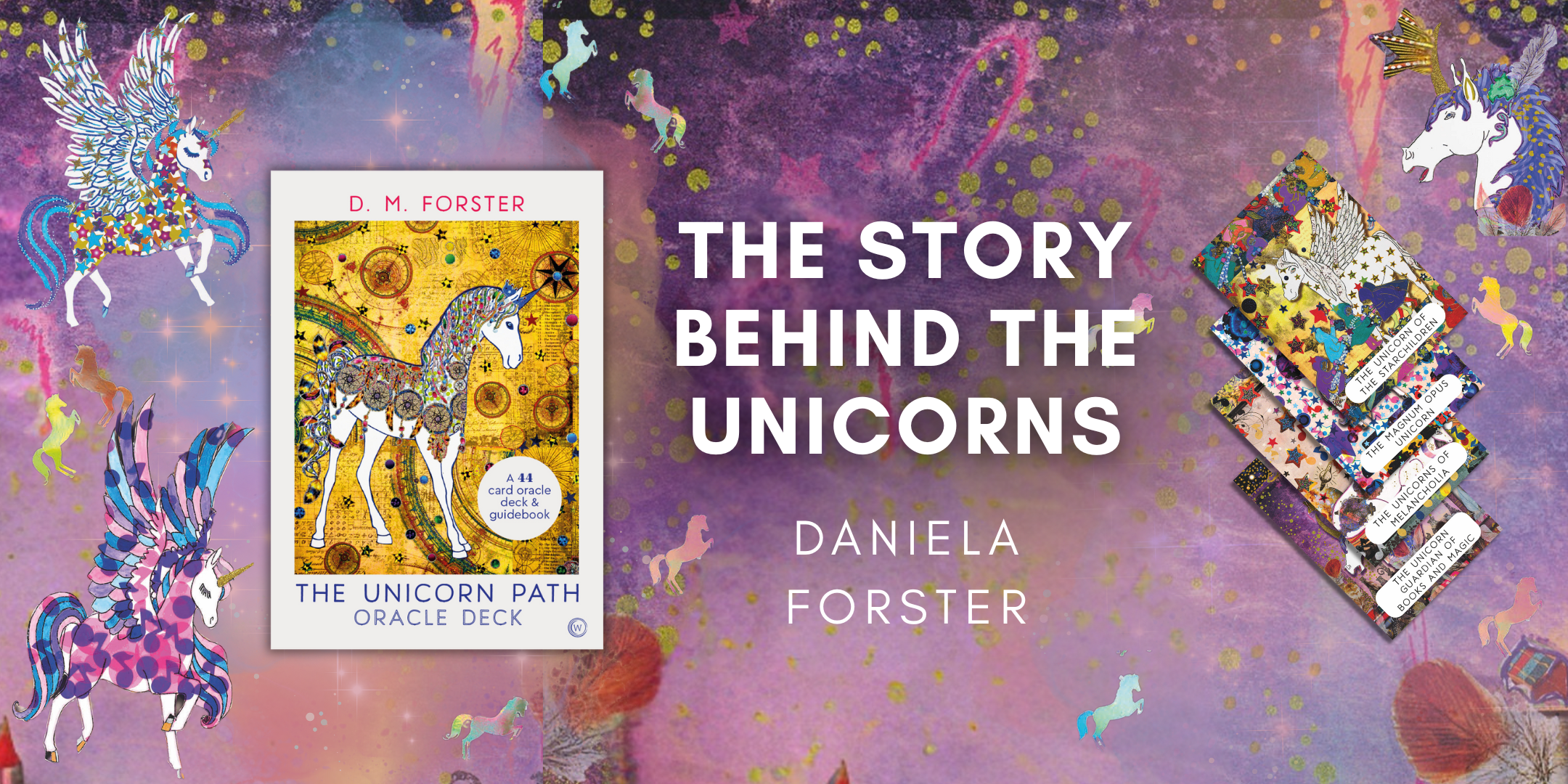

Initially, what moved me to create the Unicorn Path is the sweet song “Chloe the Unicorn”. It was a song for my friend’s child. I

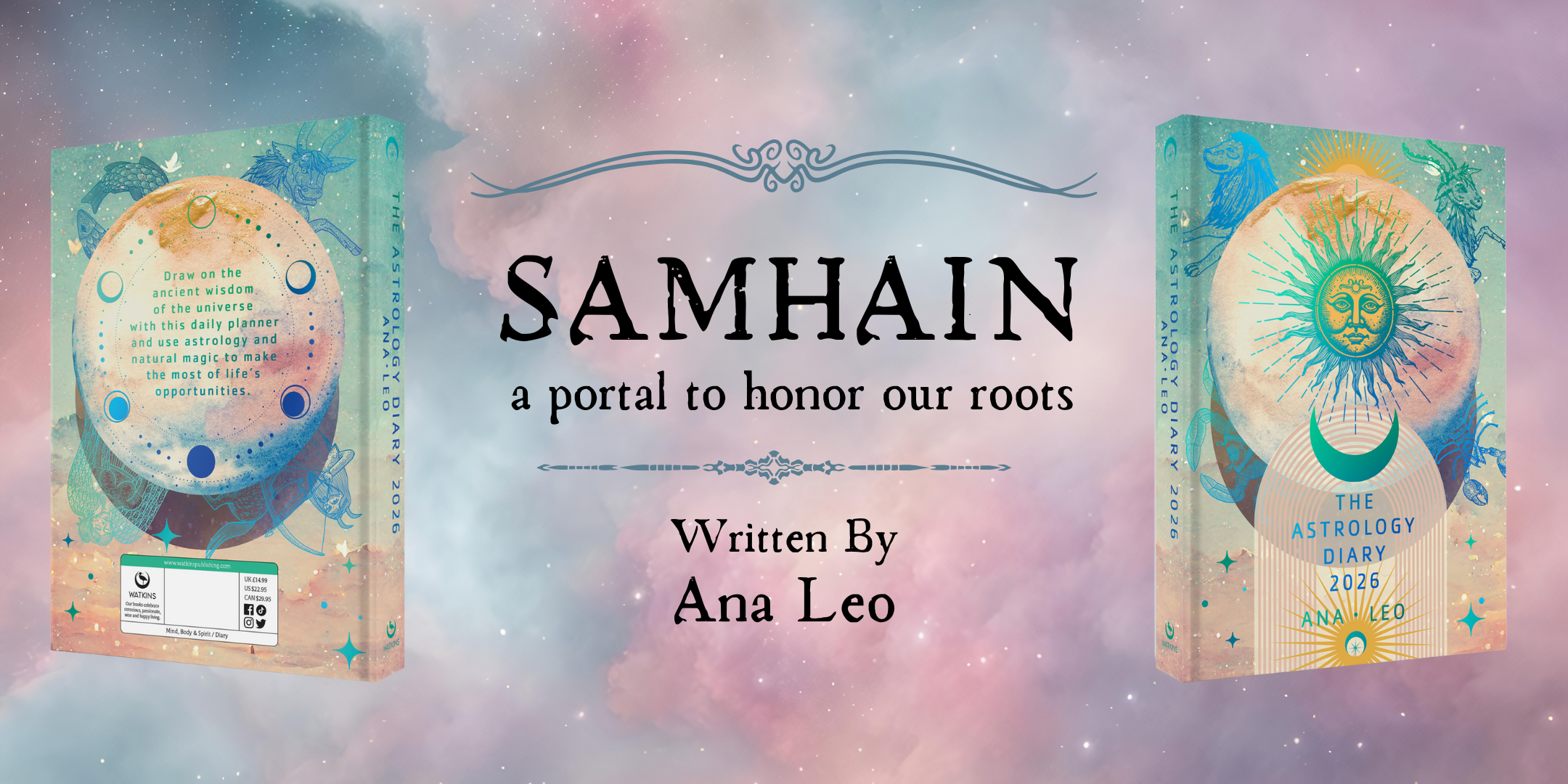

In many spiritual traditions around the world, the end of October marks a special moment. The veil between worlds becomes thinner. It is the time

"*" indicates required fields

Get a FREE eBook when you subscribe to our newsletter, and be the first to know about our new releases, exciting events and all the latest news!

"*" indicates required fields